My journey continues….

(Page 2014a)

This blog is a continuation of a series. See here (Page 2015a) for the previous blog.

Year 2015: 2nd Observation Part e

Bordering my music-making practice

As mentioned in the previous blog, I came to understand within the first few months I needed to broadly explore the fields and disciplines of contemporary music-making, in order to border – and define – my music-making practice. Due to the breadth and rapid exponential growth of the music-making industry over the past century, I felt it was necessary to review the industry, fields and disciplines of music-making.

Changing face of music-production

Perhaps motivated by the power imbalance and limited access to studios in the 1970’s and 1980’s, aligned with the broader social and cultural developments of DIY culture from the 1970s, the ever increasing available range of technology has enabled the process of music creation and production to exponentially develop, with musicians in the new era of project and mobile studios, emerging as a new generation of prosumers – both producers and consumers (Théberge 1997, P3). The acknowledged diversity of backgrounds of the contemporary DIY music production practitioner expanded to include: DJ, self-taught/school-trained and discoverer (Burgess 2013, 29).

Technological development provides multiple outcomes, including choices within music production practice: devices to use, work environment location, processes and procedures to use, skills to draw on and workflows, to name a few. In an article on best practice within the music industry, Wallis (2001, 13) observed that access to user-friendly technology has “resulted in many creative artistic talents achieving a high degree of IT literacy, leading to the emergence of the combined studio producer/ writer role. Max Martin from Sweden, writer and producer of the majority of songs recorded by artists such as Britney Spears, is such an example”. Just 5 years later, the ongoing technological developments that influence the project and portable studios further open the discipline to a broader prosumer market (Cole 2011, 448).

This in turn has attracted a range of people and what motivates them to produce music. Music production technology is now accessible to just about anyone who has any degree of interest in the creation and production of music, irrespective of their background {social status or professional role}, their musical or professional audio training and/or experience, or the genre of music they may be interested in attempting to produce, making for a truly eclectic music production society (Burgess 2014, 34; Rogers 2013). Rogers in his 2010 study on local musicians in the Brisbane scene to be of varying levels of professionalism: professional, semi-professional, emerging and several ‘non-commercial’ aspirational levels – including amateur or hobbyist practices – in the discipline (Rogers 2013, 168). I will apply the term “amateur not as a reflection on a hobbyists’ skills, which are often quite advanced, but rather, to emphasise that most of DIY culture is not motivated by commercial purposes” (Kuznetson and Paulos 2010, 295) . The “status and position of the amateur have been redeemed and a new, less aristocratic, breed of amateur has emerged .. (who) .. are technologically literate, seriously engaged, and committed practitioners”. (Prior 2010, 401).

The traditional definition of Music Producer

Traditionally, Music Producers were defined as being responsible for the: “control, guidance, and communication of the musical vision of the project”, seeing the completed product prior to the project even commencing (Gibson 2006, 1). A music producer was recognised as likely to originate from a diversity of backgrounds that would provide them with a different perspective and approaches in the studio. These background types were most commonly: artist/musician, audio engineer, songwriter, entrepreneur and multipath (Burgess 2013, 29).

A good producer was also seen to have a diversity of skills, beyond the specialist technical skills as outlined in the previous section. These skills, commonly referred to as soft skills (Page 2014b), would be:

-

understanding and proficiency of music;

-

high degree of communication skills;

-

motivational and inspirational skills to encourage greater performance and execution of roles;

-

inspirational skills to encourage a change of approach if or as required;

-

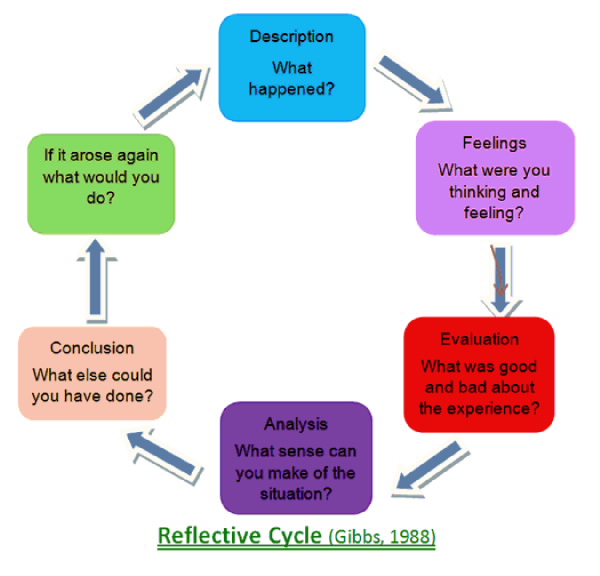

an experienced reflective practitioner;

-

project management and administrative skills to ensure the project remains viable and on target;

-

an understanding of business and have the associated skills or communication, negotiation, conflict resolution;

-

functional knowledge of the genre;

-

passion for music and all elements of the holistic music production process (Gibson 2006, 2-3; Griffin 1996, 15-19).

A new discipline of music-making emerges

Following substantial technological development from the late 1960s to today, music-making practice has diversified exponentially in a variety of social and cultural contexts (Wallis 2001; Watson and Shove 2008). Limited access to major corporate record label and broadcasting studios in the 1970’s and 1980’s aligned with the broader social and cultural developments of DIY culture from the 1970s, and with the ever-increasing available range of technology. This enabled the process of music creation and production to exponentially develop, with musicians in the new era of project and portable studios, emerging as a new generation of music practitioners (Théberge 1997, P3; Hracs 2012). A new music discipline has emerged – contemporary DIY music-making practice (Moran 2011; Watson 2014; Spencer 2005; Rogers 2013). Increased access to digital recording and production technology has enabled aspiring music practitioners from diverse backgrounds and interests to participate in a do-it-yourself (DIY) capacity, resulting in a significantly more fragmented industry (Kuznetsov and Paulos 2010; Spencer 2005; Moran 2011; Watson 2014). Wallis (2001, 13) observed that practitioners’ access to user-friendly technology has “resulted in many creative artistic talents achieving a high degree of IT literacy, leading to an even broader market”. Music production technology is now accessible to most people who have any degree of interest in music-making practice, irrespective of their social status or professional role, their musical or sonic training or experience, or the social and cultural context. This enables a truly diverse and eclectic music-making practice society (Burgess 1997, 34; Rogers 2013).

Practitioners now access and use broad range of music production and instrument technology, have vastly different workflows, for a broader range of music styles, and use a range of creative locations to create their EP’s. This diversity of practice now exemplifies contemporary industry (Ritzer and Jurgenson 2010; Purdue et al. 1997). As a result, recorded music is now created in ways that contrast with previous models, where cultural products resulted from established industrial hierarchies and imperatives (Burgess 1997).

Multiple options to play and produce music have implications on what elements of music production are used at any point in time: the creative technologies that can be used, the music style that emerges naturally out or certain technology, the creative location that practice occurs within, and the practice workflow. Further, as practitioners tend to assume all of these creative labour roles in their home-style project studios, contemporary music practitioners continue to extend their knowledge, skill level and technology, in obvious contrast with previous models (Izhaki 2013; Théberge 1997).

With the fragmentation of the industry, and the attracting diverse peoples in music-making practice, the contemporary practitioner’s motivations to practice music have also diversified. Rogers’ study highlighted varying orientations of motive amongst participants: professional, semi-professional, emerging and several non-commercial aspirational levels – including amateur or hobbyist practices. By far, the largest group was the amateur category (2013, 168). The term amateur is adopted “not as a reflection on a hobbyists’ skills, which are often quite advanced, but rather, to emphasise that most of DIY culture is not motivated by commercial purposes” (Kuznetson and Paulos 2010, 295). Not interested in the traditional music industry criteria of volume sales of commercially released tracks, these contemporary practitioners pursue music-making practice for their own motives – “their sense of identity is firmly attached to the pursuit of ‘serious leisure’” (Stebbins in Prior 2010, 401; Kuznetson and Paulos 2010, 295). The “status and position of the amateur have been redeemed and a new, less aristocratic, breed of amateur has emerged .. (who) .. are technologically literate, seriously engaged, and committed practitioners” (Prior 2010, 401).

With DIY perspectives on cultural production being particularly influential in music-making practice, in many ways redefining the field today (Frith 1992; Watson and Shove 2008; Watson 2014; Ritzer and Jurgenson 2010; Purdue et al. 1997), traditional standards of practice are now being challenged. Music industry standards (Burgess 1997, 162; Grammy Awards 2015; Gibson 2006, 42; Recording Producers and Engineers Wing 2008) appear to be less valued by DIY music practitioners. Notions of effective practice appears to be actively disregarded due to the DIY practitioners prioritizing of motivations such as creativity, emotional connection, networking, and free-spiritedness (Hracs, 2012; Kuznetsov and Paulos 2010). Burgess found contemporary music practitioners are likely to be: self-taught, and of a ‘discoverer’ learning style (2013, 29); with a preparedness to reject accepted industry practice (eg: technical or music style standards); and a willingness to borrow at will any music or sonic characteristics from other cultural approaches to fuse into their practice, leading to “unprecedented diversity” (Rogers 2013, 168; McWilliam 2008, 38; Davie 2012, 41).

With this diversity comes the portability of both production and performance technology. For example; producing a full EP on a beach, only needing to retreat to a location to get some electricity when my laptop battery runs empty; dance festivals in a forest where the artists arrive with as little gear as a laptop, or perhaps a USB stick and perform in front of 1,000 people for up to several hours; or, as a result of the technological developments, a new music style emerges because practitioners use the digital virtual technology as an instrument and performance tool, rather than for what it was originally designed for by the manufacturer {data management} (Hewitt 2008, xv). One of the best examples of this would be the creation of electronic music and its sub-genres of electronic dance music, trance music and chill music.

It could also be stated that in Electronic Music Production (EMP), musicians and producers generally use portable technology, accessing synthetic or digital instruments, and compose typically in a structured process (Gunderson 2004; Johnsen et al 2007; Davie 2014, 38; Duckworth 2005, 148; Goyte 2011a; Goyte 2011b; Davie 2015, 34; Holder 2011; Huber and Runstein 2014, 78). In contrast, Indie Rock musicians and producers generally use project studios, access acoustic or electric instruments, and quite often compose in an organic process (Emerick and Massey 2006, 306; Burgess 2014, 93; Dandy Warhols 2010; Leyshon 2009, 1309; Davie 2012, 44-45; Tame Impala. 2012).

The contemporary music-making practice

I propose contemporary DIY music-making practice is now positioned in large part due to factors including, the DIY cultural focus of the past 4 decades, spurred significantly from the punk music era of the 1970’s, where independence and expression was held in greater regard than either aesthetics, musical training or performance technique [DIY cultural pursuit as continued agency of change], and; the simultaneous technological development of the equipment and tools contemporary musicians as music producers use, facilitating unrivalled levels of access to professional equipment, significantly influencing the manner in which musicians as music producers engage in their practice (Wallis 2001). [technology as agent of change]. Additionally, effective contemporary DIY music production practice potentially has the following characteristics:

-

The practitioner is a prosumer, using professionals tools, but also be a consumer of the new technologies [technology as agency of economic change];

-

The practitioner interacts with the technology as a medium for creative expression, as if it were an instrument [technology as agency for creativity and differentiation];

-

The practitioner works in varied environments, use different processes, skills and workflows in order to achieve the outcomes that the musicians and music producers would have a decade ago {and probably including a portable environment} [technology as agency of change].

-

The practitioner works across varied genres, requiring different workflows and instruments

-

The practitioner works with a variety of technologies, likely to be a combination of digital, digital virtual and analogue equipment

-

The practitioner works with a combination of acoustic, digitalised and synthetic instruments

In framing my research study, I have broadly and deeply researched the technological advancements historically in the following audio and audio-related areas of: the telephone; the telegraph; the phonograph; microphones; gramophones; the recording process; the development of radio stations and broadcasting; the development of recording and recording studios; the development of alternative electronic instruments such as synthesisers, organs and samplers; recording consoles, multi-track recording devices, popular music production, large format console studios and analogue audio processing equipment; general computers and Apple Macintosh computers; the internet; digital instruments such as digital sequencers and samplers; digital consoles and audio processing equipment; virtual soft samplers and instruments; virtual Digital Audio Workstations {‘DAWs’}, and a range of exemplar artists (commercially successful, full-time practitioners) that were innovative in some way, influenced by the technological developments, and incorporated the new technologies into their creative works for either new or unique sounds, and/or improved workflow.

The contemporary music-making practitioner

Having explored how the technological development of general devices (namely personal computers and sound cards) and music-making equipment (namely samplers and digital interfaces), has had on, and continues to have on, the music production process, lets look at a profile of the contemporary DIY music production practitioner and the technology they use, we have unearthed to date.

The contemporary DIY music production practitioner may be of any age, of any social status or professional role, but are likely to be IT conversant. They are likely to come from a range of backgrounds such as: artist/musician, audio engineer, songwriter, DJ, self-taught/school-trained, discoverer, entrepreneur or multipath (Burgess 2013, 29). The contemporary DIY music production practitioner is likely to have at the very least a portable studio, or perhaps a project studio with a range of both outboard and in-the-box instruments and audio processing devices, or quality ranging from entry level, through to professional level. I believe that the term prosumer accurately describes the contemporary DIY music production practitioner, one who is both a purchaser and an operator of technology aimed at the level of domestic, semi-professional or professional use. This technology could be analogue, digital or virtual, procured as a DIY kit, as an assembled device via retail channels, or procured through a range of file share, shareware, or freeware, either legally or not. anti-consumerism, rebelliousness, and creativity. They most certainly possess a ‘just do it’ spirit as the Nike slogan has encouraged since 1971.

They may or may not be currently a professional or a semi-professional DIY music production practitioner, they may or may not be motivated by commercial aspirations to become a professional or a semi-professional DIY music production practitioner. They may be motivated by purely creative or social aspirations, operating on a non-commercial basis, at an amateur or hobbyist level. Kuznetsov and Paulos found the majority of DIY communities engaged “to express themselves and be inspired by new ideas”, “not to gain employment, money, or online fame” with an example being “amateur radio hobbyists in the 1920’s” (2010, 295). Operating at this amateur level does not however reflect their level of passion or commitment compared to the professional practitioners, just the reliance on alternative forms of income to fund their contemporary DIY music production practice.

If the contemporary DIY music production practitioner does have professional aspirations, they are more than likely an ‘entrepreneurial’ producer, “who must increasingly not only perform creative tasks, but also a range of business including searching for work, self-marketing and managing the finances of small studio facilities. This mirrors the increased entrepreneurialism found among independent musicians” (Watson 2013). I would argue, that in these times of tasking multiple roles in economically tight times (as Braithwaite alluded), the choice of music production environment and music production process comes down to what resources are available, how much time one has, and access to funds to support their passion (Théberge 2012). However, as the contemporary DIY music production practitioner is a resourceful species, in the new economy restraints of budget no longer guarantee there will be limitations of access as previous generations of aspiring music producers experienced. A slogan of DIY practitioners in the new economy may be ‘where there is a will, there is way’. With access, comes choice: choice of technology, location, musical style and workflow. These elements of practice provide each practitioner many combinations of options to apply to their practice, enabling uniqueness in process, sonics and musical style. Yes, the discipline of contemporary DIY music production is now “characterized by infinite choice” and as a result of the burgeoning numbers of practitioners, “intense competition” to have their music heard, irrespective of commercial or non-commercial motives. As a result, practitioners need to expand their focus from production to also include promotion, developing “strategies to ‘stand out in the crowd’” (Hracs et al 2010, 1,144).

This blog series is planned to continue next month with Doctoral Research Study – Part 2f (Page 2015b). It is intended for this blog series to continue on a regular basis as I progress through my doctoral research project.

References

Burgess, Richard James. 2014. The history of music production. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burgess, Richard James. 2013. The art of music production: the theory and practice. New York: Oxford University Press.

Burgess, Richard James. 1997. The art of record production. London: Omnibus Press.

Cole, S. J. 2011. “The Prosumer and the Project Studio: The Battle for Distinction in the Field of Music Recording.” Sociology 45 (3): 447–463.

Dandy Warhols, The. 2010. The Dandy Warhols: best of the capitol years 1995-2007. Capitol Records. Compact Disc.DIY image courtesy of: DIY Accessed 5th May, 2015

Davie, Mark. 2015. “DIY: don’t be a tool.” Audio Technology2015 (106): 98.

Davie, Mark. 2014. “Danger Mouse: producer of the decade.” Audio Technology (100): 98.

Davie, Mark. 2012. “The diy revolution.” Audio Technology (91): 98.

DIY image courtesy of: DIY Accessed 5th May, 2015

Duckworth, William. 2005. Virtual music: How the web got wired for sound. New York, NY: Routledge.

Emerick, Geoff and Howard Massey. 2007. Here, there and everywhere: my life recording the music of the beatles. New York, NY: Gotham Books.

Frith, Simon. 1992. “The industrialization of popular music.” Popular Music and Communication 2: 49-74.

Grammy Awards. 2015. “The 2015 Grammy Awards.” Accessed 20th April, 2015. https://www.grammy.com/nominees.

Griffin, RW. 1996. Management. 5th ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Hewitt, Michael. 2008. Music theory for computer musicians. Boston: Cengage Learning Course Technology.

Huber, David Miles and Robert E Runstein. 2014. Modern recording techniques. 8th ed. Burlington: Focal Press.

Gibson, Bill. 2006. The s.m.a.r.t. guide to becoming a successful producer/engineer Boston: Thompson Course Technology.

Goyte. 2011b. Making Mirrors. Eleven May 5, 2015. Compact Disc.

Gunderson, Philip A. 2004. “Danger Mouse’s “grey album”, mash-ups, and the age of composition.” Postmodern Culture 15 (1): 7. doi: 10.1353/pmc.2004.0040.

Holder, Christopher. 2011. “Goyte.” Audio Technology (84): 98.

Hracs, Brian J. 2012. “A creative industry in transition: the rise of digitally driven independent music production.” Growth and Change 43 (3): 442-461.

Izhaki, Roey. 2013. Mixing audio: concepts, practices and tools. 3rd ed. Oxford: Focal.

Kuznetsov, Stacey and Eric Paulos. 2010. “Rise of the Expert Amateur: DIY Projects, Communities, and Cultures.” In Proceedings of the 6th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Extending Boundaries, Reykjavik, Iceland, October 16-20, 2010, edited, 295-304. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=1868914&picked=prox: ACM.

Leyshon, Andrew. 2009. “The Software slump?: digital music, the democratisation of technology, and the decline of the recording studio sector within the musical economy.” Environment and Planning 41 (6): 1309.

McWilliam, Erica. 2008. The creative workforce: how to launch young people into high-flying futures. Sydney: UNSW press.

Moran, Ian P. 2011. “Punk: the do-it-yourself subculture.” Social Sciences Journal 10 (1): 13.

Onion image courtesy of: Onion Layers Accessed 15th December, 2014

Page, David L. 2017 2nd Observation image courtesy of David L Page Created 10th June, 2017

Page, David L. 2014a image courtesy of David L Page Created 15th December, 2014

Prior, Nick. 2010. “The rise of the new amateurs: Popular music, digital technology and the fate of cultural production.” Handbook of cultural sociology. London: Routledge: 398-407.

Purdue, Derrick, Jörg Dürrschmidt, Peter Jowers and Richard O’Doherty. 1997. “DIY culture and extended milieux: LETS, veggie boxes and festivals.” The Sociological Review 45 (4).

Recording Producers and Engineers Wing, The. 2008. “Digital Audio Workstation Guidelines for Music Production.” Accessed May 27, 2015. https://www.grammy.org/files/pages/DAWGuidelineLong.

Ritzer, George and Nathan Jurgenson. 2010. “Production, consumption, prosumption: the nature of capitalism in the age of the digital ‘prosumer’.” Journal of Consumer Culture 10 (1).

Rogers, I. 2013. “The hobbyist majority and the mainstream fringe: the pathways of independent music-making in Brisbane, Australia.” In Redefining mainstream popular music, edited by Sarah Baker, Andy Bennett and Jodie Taylor, 162-173. New York: Routledge.

Spencer, Amy. 2005. DIY: The rise of lo-fi culture: Marion Boyars London.

Tame Impala. 2012b. Lonerism. Modular. Compact Disc.

Théberge, Paul. 2012. “The end of the world as we know It: the changing role of the studio in the age of the internet.” In The art of record production: an introductory reader for a new academic field, edited by Simon Frith and Simon Zagorski-Thomas, 77-90. Farnham, Surrey: Ashgate.

Théberge, Paul. 1997. Any sound you can make: making music/consuming technology. Hanover: University Press of New England.

Wallis, R Dr. 2001. “Best practice cases in the music industry and their relevance for government policies in developing countries.” Paper presented at the United Conference on Trade and Development, Brussels, Belgium, May 14-20, 2001.

Watson, Allan. 2014. Cultural Production in and Beyond the Recording Studio. New York, NY: Routledge.

Watson, Matthew and Elizabeth Shove. 2008. “Product, Competence, Project and Practice DIY and the dynamics of craft consumption.” Journal of Consumer Culture 8 (1): 69,74.

– @David L Page 20/05/2015

– updated @David L Page 30/05/2015

– updated @David L Page 10/06/2017

Copyright: No aspect of the content of this blog or blog site is to be reprinted or used within any practice without strict permission directly from David L Page.

SaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

SaveSaveSaveSave

(Tingen 2014)

(Tingen 2014)

(Meter 2014)

(Meter 2014)